Written By: Patrick Brown and William Harding

Childs v Desormeaux remains the leading authority on social host liability. In Childs, it was found that social hosts do not owe a duty of care to people that are injured by the actions of individuals that became intoxicated while attending the social host’s party. In that decision, former Chief Justice McLachlin stated:

“hosting a party at which alcohol is served does not, without more, establish the degree of proximity required to give rise to a duty of care on the hosts to third-party highway users who may be injured by an intoxicated guest” (emphasis added)

The understanding from the inclusion of “without more” is that although no duty was found in Childs, given the right set of facts a duty may be owed by social hosts. Since the date of that decision, now over 10 years ago, many attempts have been made to meet the narrow exception left open by Childs.

Our recent decision from the Ontario Court of Appeal is one such example. In Williams v Richard, Mr. Williams became intoxicated when he consumed approximately 15 beers over the course of three hours at the home of his friend, Mr. Richard. Shortly after leaving the Richard residence, Mr. Williams loaded his young children and their babysitter into his car and proceeded to drive the babysitter home. On his way back to his house, he was involved in a collision in which his children suffered injures. Actions were commenced against both Mr. Richard and his mother.

The Defendants brought a summary judgment motion stating that no duty was owed by the Defendants to the injured children. The motions court judge granted summary judgment stating that a duty of care could not be established and even if a duty did exist, that duty ended once Mr. Williams arrived home to pick up his babysitter and children. This ruling was then appealed.

The Court in allowing the appeal, highlighted many key factual differences between this action and Child’s. For example, in the present case it was obvious to Mr. Richard that Mr. Williams was quite intoxicated when he was leaving his home. Unlike Childs, this was not a BYOB party with multiple guests. The beer consumed by Mr. Williams was provided by Mr. Richard and consumed in the presence of Mr. Richard, so there could be no illusions in the mind of Mr. Richard as to exactly how much Mr. Williams had to drink. At paragraph 34 Justice Hourigan states:

“The motion judge did not advert to or consider the obvious factual differences between the cases. This was not a large social gathering, rather it was two men drinking heavily in a garage. There was a developed pattern of this behaviour, enough so that the men had a pact as to what to do in the event one of them drove children while under the influence. Alcohol was provided or served, to a certain extent, as the garage refrigerator the men were accessing had 30 to 40 cans of beer in it. These facts distinguish the case at bar from Childs.”

Additionally, Justice Hourigan rejected the motion judge’s finding that any duty ended once Mr. Williams arrived home stating “there is no automatic rule that the duty of care expires once the intoxicated driver arrives home safely.”

This decision acknowledges that given the right set of facts, a social host may owe a duty of care to injured third parties. Those hosting functions involving alcohol should be prepared to make the necessary arrangements for intoxicated guests when warranted. This decision is also important as it makes clear that an intoxicated individual arriving home does not automatically bring a host’s duty to an end. This has implications for other types of cases such as over-serving at a bar or restaurant.

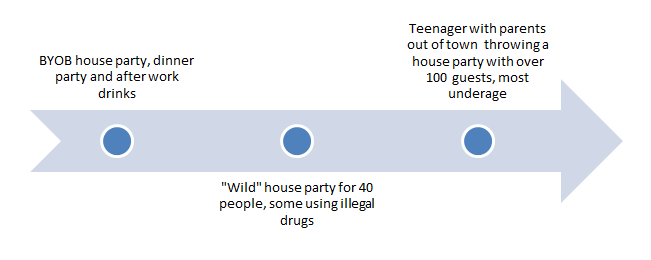

Lastly, the Court outlined the spectrum of facts that may or may not constitute the requisite “something more” and cause a social gathering to become an “inherent and obvious risk” including:

- Whether alcohol was served at the party or were guests invited to bring their own alcohol

- The size and type of the party

- Whether other risky behavior is occurring at the party (such as underage drinking or drug use)

The court also provided examples from case law, and explained where they fall on the “inherent and obvious risk” spectrum.